In my book, The Power of Little Ideas, I explain how companies should execute the “Third Way” approach to innovation, and how dramatically it can affect the fortunes of a company that does it well. One of the lead stories in the book was going to be MakerBot – a 3D printer company headquartered in New York. But as I was writing the book, the company imploded, despite having executed the Third Way approach very well. The story of Makerbot is instructive for anyone trying to implement the Third Way.

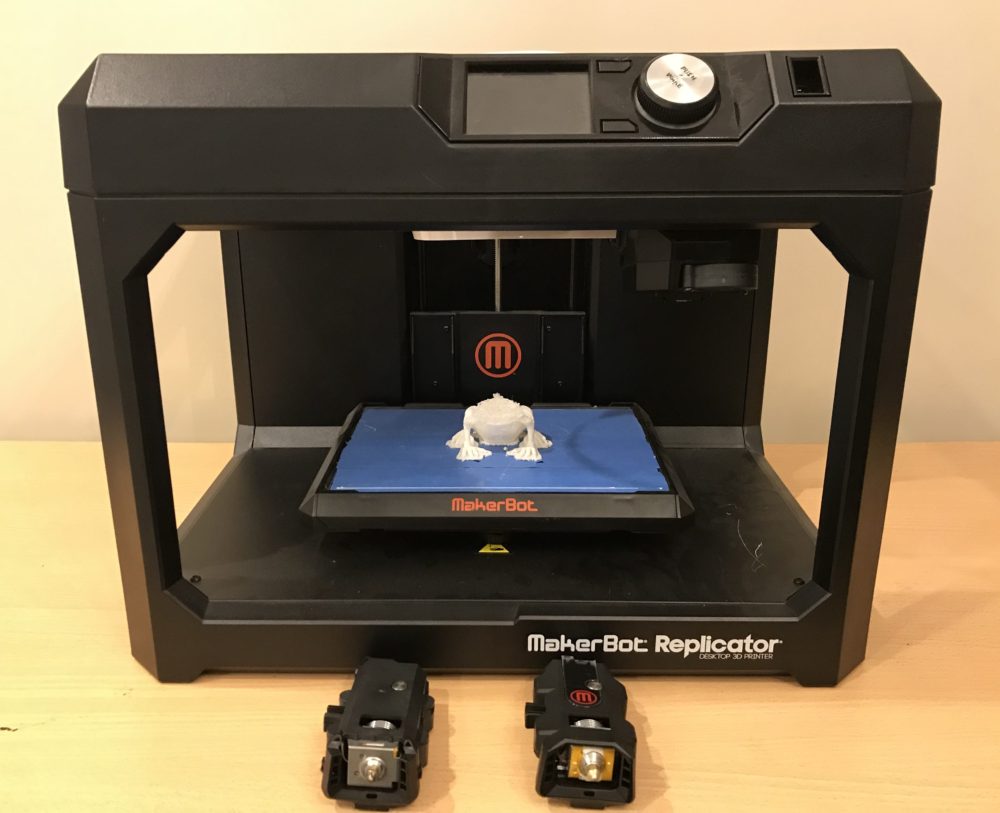

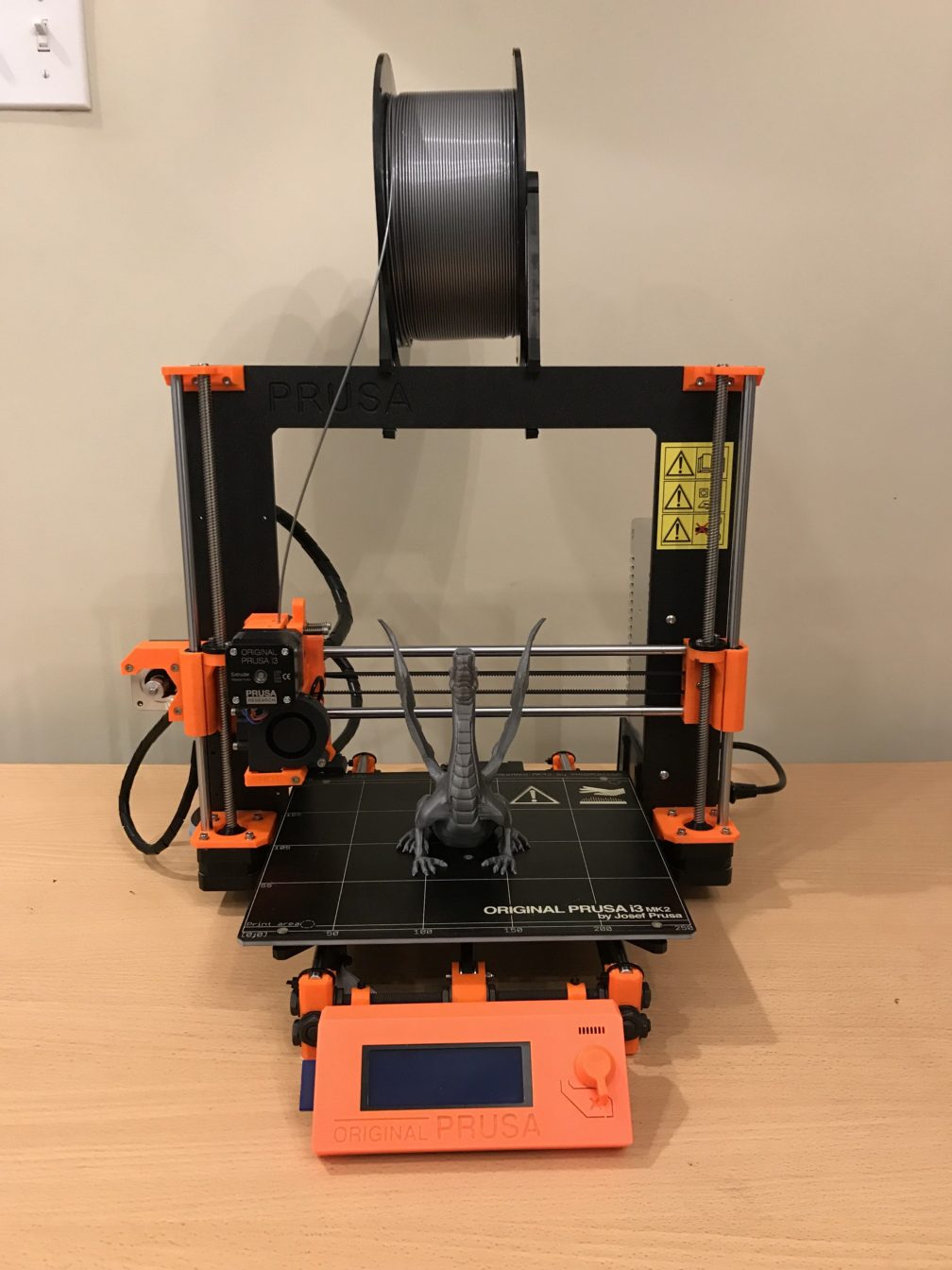

I know the Makerbot story well, as I’ve owned four consumer-grade 3D printers: three Makerbots and one Prusa MK2S. I bought a Makerbot Cupcake in 2009, the Makerbot Replicator in 2012, a 5th Generation Makerbot in 2015, and the Prusa MK2S in December of 2017. The first machine – the Makerbot Cupcake – never worked well, but I never expected it to. It was a hobbyist toy: it was unreliable, the quality of the parts it produced was poor, and the machine was expensive. But it was a wonderful introduction to 3D printing. By assembling the printer from a kit, you learned how 3D printers worked. I was able to print a few simple things – a whistle, bottle opener, and a few other small items. My second printer, the Makerbot Replicator, was an amazing improvement; it was more reliable, higher quality and featured two extruders that allowed for printing in two different colors. In March of 2015 I purchased my third Makerbot, the Makerbot 5th Generation printer.

Makerbot invented the market for consumer-grade 3D printers, and owned a 25% market share as late as 2013 in a rapidly growing market. Just four years later, the company’s share was below 5%, its reputation was in tatters, and the founder had been let go.

What went wrong at Makerbot? How could a company that executed the innovation strategy I’m advocating perform so badly? The problem: the product was lousy. If the product doesn’t work, it doesn’t matter how strong your complementary innovations are and how well you support the overall customer purchase and use process.

It’s worth going back to the beginning to review how dominant a force Makerbot was in the industry, and how quickly it all fell apart for the company.

A quick history of Makerbot and consumer-grade 3D printing

In the late 1980s, S. Scott Crump developed fused deposition modeling (FDM), the form of 3D printing in which an extruder lays down layers of plastic to make a model, and commercialized it by founding Stratasys in 1989. In 2005, a British initiative attempted to create an open-source 3D printer based on this technology, made almost entirely of components it could print, essentially to create a self-replicating machine. This initiative, which came to be known as the RepRap project (for REPlicating RAPid-prototyper) is still going today.

Bre Pettis, a former schoolteacher from Seattle, moved to New York City to make videos for Etsy, and started a hackerspace called NYC Resistor. Through NYC Resistor, he began working on the RepRap project along with Zach Hoeken Smith and Adam Mayer. Over time, their focus shifted away from the RepRap project to making better, less expensive printers. The trio secured some angel investment and founded MakerBot in 2009.

The group produced their first product, the Cupcake, a kit based on FDM technology that customers assembled themselves (my first 3D printer). This initial product was more successful than they had expected, and soon the company was expanding and creating new versions of the printer. Their next kit, the Thing-O-Matic, was released in 2010 with a 100x100x100mm (about a four-inch cube) build envelope, and was completely open-source, as was the Cupcake. This was followed in January 2012 with the Replicator, a paradigm shift for MakerBot. With the Replicator, the company began moving away from the kit sales format. The Replicator was designed to work as soon as users opened the box and was targeted at people more interested in designing and printing than in tinkering with hardware. The Replicator remained open-source, and also more than doubled the build envelope (the size of the parts that could be built) of the Thing-O-Matic.

But Makerbot didn’t confine itself to making hardware. To encourage use of its machines and share the designs of the user community, MakerBot Industries launched the web site Thingiverse. Thingiverse is an online forum and community where members can swap, share, and discover 3D designs that can be printed outright, modified by anyone, and cooperatively improved. The site initially aimed to have all its content available through Creative Commons licensing, allowing free use and distribution. To this day it remains a massive repository and source of material for the owners of 3D printers.

In September 2012, the Replicator 2 was released. This product continued to improve the core offering of MakerBot, as the build envelope was again increased, along with a host of other improvements, such as smaller layers, improved electronics, a better display, and more. While designed to be easy to use right out of the box, requiring little tinkering or adjustment, this machine limited the input material to PLA plastic. MakerBot became known for its strong customer support, a vibrant ecosystem of partners, and reliable, proven hardware design. This was a great value proposition to the designer, schoolteacher, or people interested in printing out their own creations but not a part of, or perhaps even familiar with, the RepRap movement.

In 2013, MakerBot grew its product line further by introducing the Digitizer, a 3D laser scanner with integrated turntable that could provide a 3D rendering of any object that fits on it. The 3D rendering files can then be modified, posted on Thingiverse, and printed. The scanner one-upped a variety of open-source and hacked solutions. The Digitizer not only improved the quality of scans, but its primary improvements were its ease-of-use and seamless integration with the MakerBot hardware and software. The technology itself was not revolutionary. The innovation was important, but incremental, and its strength was its complementary nature to Makerbot’s products, software, and Thingiverse.

Makerbot also invested resources in developing proprietary software along with its hardware. MakerBot Desktop was a powerful software package that allowed users to discover, manage, share, and send designs for printing, during which time they can be monitored from the software. The company also developed a mobile app that allowed users to check on prints and search the Thingiverse for objects. Finally, MakerBot announced a Developer program; the company released APIs and documentation and offered discounted machines for testing.

At the same time, MakerBot opened retail stores that let potential customers learn how 3D printers work, watch them in action, and see how one might be useful, or just plain fun, to have in their own homes. While an incremental innovation, this move strongly reinforced the brand and the ability of MakerBot to sell to those new to the 3D printing market. No other 3D printing company had a brick-and-mortar presence at the time.

In 2014, MakerBot continued to expand its core product line with the fifth generation Replicator Desktop Printer. The new feature for this generation of the printer was the Smart Extruder; Makerbot packaged the most problematic parts of the printer – the filament feed mechanism and heated extruder – into an easily swappable module and sold replacements for the module. The company also expanded its product line, offering smaller (the Replicator Mini) and larger (the Replicator Z18) versions of its printers.

Meanwhile, Makerbot also revved up its efforts to develop complementary innovations that would make its core products more useful. For example: MakerBot worked to grow its sales to high school and college classrooms in order to fulfill what it saw as an important application of its easy-to-use hardware and software. To serve this market, the company created the MakerBot Academy with the goal of getting at least one device into every school in the United States. The company offered a MakerBot Academy bundle that included a fifth-generation Replicator, filament, and protection plan. It partnered with DonorsChoose.org, a company that allows nonprofit organizations to quickly set up fund-raising campaigns. MakerBot let teachers request assistance in purchasing a Makerbot bundle and host a crowdfunding campaign to raise the money for the purchase.

In addition to its vast and growing free offerings in the Thingiverse, MakerBot opened a digital store on Thingiverse selling highly detailed and collectable designs that could be printed on any 3D printer. Users could purchase, download, and print licensed material such as Sesame Street figurines. This created another revenue stream for MakerBot and also brought product licensing to 3D printing in order to make its latest Replicator products more appealing to consumers.

2015: The year it all falls apart for Makerbot

At the beginning of 2015, I was looking for a unique assignment for my MBA class in product design and development. I decided to challenge the class to develop a product that could be produced on a 3D printer. In March of 2015 I purchased a Marketbot 5th Generation printer. It was expensive, unreliable, and not user-serviceable. The printer cost $3499, plus $399 for a service plan, $48 for filament, and $222 for an extra Smart Extruder. That’s $4145 without tax. One of the major innovations in the printer was the “Smart Extruder,” a self-contained module that could be swapped out if it jammed or clogged. The problem was that most extruder problems are easy to fix if you can disassemble the extruder. But with the Smart Extruder, when there was a jam, you had to remove the extruder and mail it to Makerbot for repair. The extruder was poorly designed and jammed frequently, meaning that you had to buy several extras (at more than $200 each) if you wanted to keep the printer running.

After a year, the company fixed some of the problems with the Smart Extruder, and the printer became more reliable. But it is still a terrible printer. Despite having several years to fix the problems, it is only the 73rd highest-rated printer in 3D Hubs’ 2018 annual ratings of printer quality.

In December of 2017, I purchased my fourth printer – the Prusa MK2S – for $599, about 1/7 the cost of the Makerbot. It is better in every way. It’s faster, quieter, more reliable, and produces higher quality results.

For a time, Makerbot was the dominant force in the fast-growing 3D printer industry. In 2011, the company had a dominant 40% market share. However, when the quality of the printers declined, that number declined dramatically. By the end of 2017, the percentage of Makerbot printers available for use on 3DHubs – number that includes all printers sold in all the prior years – had declined to 4.9%.

As I discussed in The Power of Little Ideas, companies such as LEGO, Novo Nordisk, and Gatorade successfully used the Third Way to surround their core products with complementary innovations to boost sales and profits. What these and other successful companies have found is that focusing on core products and innovating around them is a low-risk, high-reward approach to innovation. Makerbot Industries executed this strategy well, but forgot to maintain the quality of its core product. No amount of effort developing complementary innovations can save a poor product.